Anticipating responses for stronger messages

Now that you know more about who you are trying to engage, you need to figure out what is going on inside their brains that will make your message successful or a complete disaster (or somewhere in between).

I often run meetings. Inevitably, I have to give people breaks or they will die. So I do. Now, I know if I say, “Back in 15 minutes ready to roll,” I will easily be missing half the group in 15 minutes and we’ll get behind schedule. I need to understand how their brains will respond to my direction and what they are seeing their peers do. This is where understanding what is at play might help. Some people will not immediately go check email or use the restroom. They will start networking. That means when I call the room to order, they will then dash out to take care of business. Some people wait until most other people sit back down before they join. So the sooner I get the majority seated, the better my chances of restarting. And last, breaks are more fun than work. People naturally want to stay on them longer. Knowing all this background and what is likely to play out helps me think through my messaging. I could give them a shorter break—say 10 minutes instead of 15—knowing it will take me five minutes to corral everyone back for the reasons above. I might offer them an incentive that makes them want to be back in their seats at the right time and not miss something compelling. I could offer a disincentive like, “I am locking the doors at a certain time so we stay on track.” I could designate a few colleagues to round up the participants as I know people like to comply with polite requests from peers. I have many options. But I definitely need to employ one or more of these. Otherwise, when I send people on break, we are going to be late getting started again.

You need to do this level of analysis any time you want to ask people to do something. Anticipate responses in order to get the outcomes you want. Start with understanding what’s at play.

Know what’s at play

To know how your messages might land, you need to know who your audience is and respect that (see above about psychographics). You also need to know what is at play in people’s minds and what obstacles you might trigger when you engage with them. As behavioral sciences evolve, the possibilities grow. Here are some likely responses you can plan for.

Let’s say you want to make a big change. Think Obamacare, massive education reform or banning fossil fuels. You can anticipate some of the reactions audiences you want to engage may have. For instance, it may start off positive. People often have optimism bias, which means they overestimate that something good will happen and underestimate that it won’t. This is why, despite the fact that a majority of restaurants close in the first year, people still open new ones. But people will also embrace the status quo. Research shows that people often make the leap from what is and equate it to what ought to be. This is how we still have child labor or child marriage in some places. People believe this is how it was meant to be. And before you start shaking your head since we don’t have child labor in the U.S., think about the shirt you are wearing. Chances are it is made by people, possibly children, who get paid pennies in dangerous factories. You know cheap labor has ethical problems but perhaps you rationalize that, “They wouldn’t get jobs otherwise” or “You can’t know where everything you buy comes from.” Whatever the excuse, you are rationalizing the status quo. When considering change, people will also see if it fits with their worldview, reinforces a badge they wear and if their tribe is following suit. Let’s take bike shares. This is a big change. We used to buy our own bikes or walk. Now there are communal bikes. For Millennials who are growing up in a sharing economy, this fits their worldview that we should have access to things when we need them without owning them, it reinforces some of their badge of being urbanistas and resisting car culture, and they see many people who are just like them coasting around town on bikes. With big change, you’ll also encounter loss aversion. Loss aversion happens because when there’s change, people worry too much about what they’ll lose instead of considering what they’ll gain. In the case of Obamacare, they worry more about possibly having to change doctors than the fact they might save a lot of money on their healthcare. Your benefits messaging may fall on deaf ears if you don’t mitigate the loss aversion a proposed change will trigger, as well as the biases your audience brings to the party including a tendency to embrace the status quo.

Let’s look at another one. Imagine you are working on a big, intractable problem like poverty, climate change or the refugee crisis. The first psychological force you may encounter is what Steven Pinker in his book Better Angels of Our Nature calls compassion fatigue. As a New York Times article exploring this says: “The public has a similar reaction to mass joblessness and starving countries alike: the problems sap the imagination in part simply because they are daunting and have not responded well to previous efforts. We have already pumped billions into each, with little visible effect. If only they would cancel their next emergency.” Paul Slovic studies a similar but different effect he calls “psychic numbing.” His studies show that when people see one child suffering, they are likely to care, donate and give money. Once you start showing lots of children, the interests and actions drop off because of psychic numbing. It is people’s response to seeing too much and feeling too much and is a survival instinct. Unwittingly, your messaging may lead to more fatigue or numbing which will make it harder to mobilize people.

You may also encounter short-termism. This is where people over-value that which they see as closer to them in time and space. When dealing with people and climate change, this is what happens when you use polar bears. For most people, polar bears are very far away. This makes the issue seem distant, less personal and less immediate. When you show a city similar to the one they live in that’s been devastated by a recent superstorm, they are much more likely to see the issue as close, personal and one they should pay attention to.

You can do this same state-of-play assessment on specific issues. Let’s say you want to stop over-incarceration. First, if you talk about numbers more than people, you may encounter a lack of empathy to the point that audiences dehumanize populations. When people start to dehumanize people, they can start “othering” them. When we make people “others,” we are willing to create different rules and accountability than we might for ourselves and the people we see as like us. We have seen this throughout history, from slavery to denying women the vote to blocking gay people’s rights. You see it in criminal justice, where many states prevent former felons from voting despite the fact that they’ve done their time and are re-integrated into society.

When you talk about reducing sentencing for non-violent criminals, people may accept that. But when you start talking about reducing sentences for violent offenders you may trigger moral panic. Moral panic happens when one person becomes a symbol for everything that you fear may happen. Case in point: In August 2016, basketball player Dwyane Wade’s cousin was shot and killed purportedly by two men who were out on parole, after having been imprisoned because of gun convictions. A story like this does not mean that the majority of those out on parole will commit crimes. But moral panic can set in and people wanting to stop sentence reduction efforts can use such stories to fan the flames in their effort to get the public to reject calls for reform.

You also need to carefully consider the timing of your messaging. When we combine messages with timing triggers, we make it more likely audiences will act. For example, if we ask people to register to vote when they are in the car driving, they are unlikely to pull over. However, if we ask them to visit an online site and register to vote for the people who will decide the city’s transit options while they are riding the bus, we are using a timing trigger to remind them how important transit decisions are to their life.

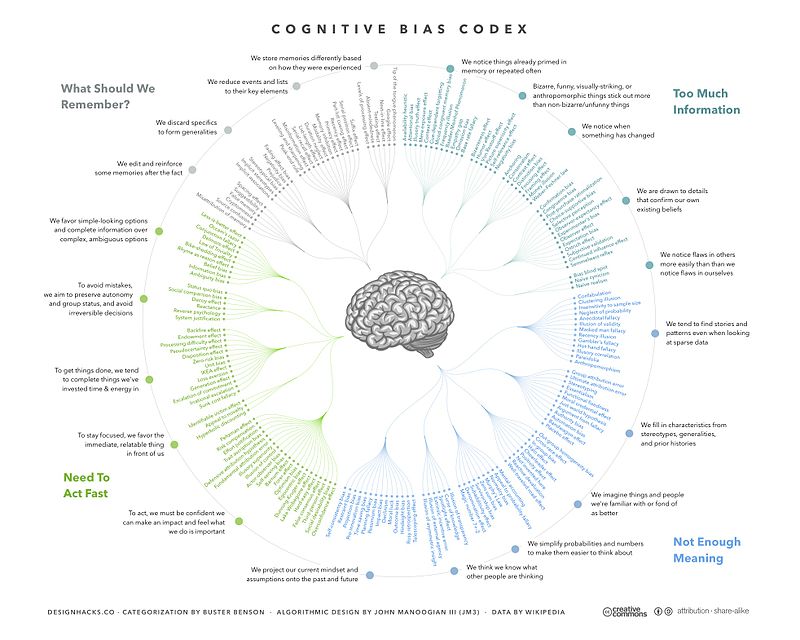

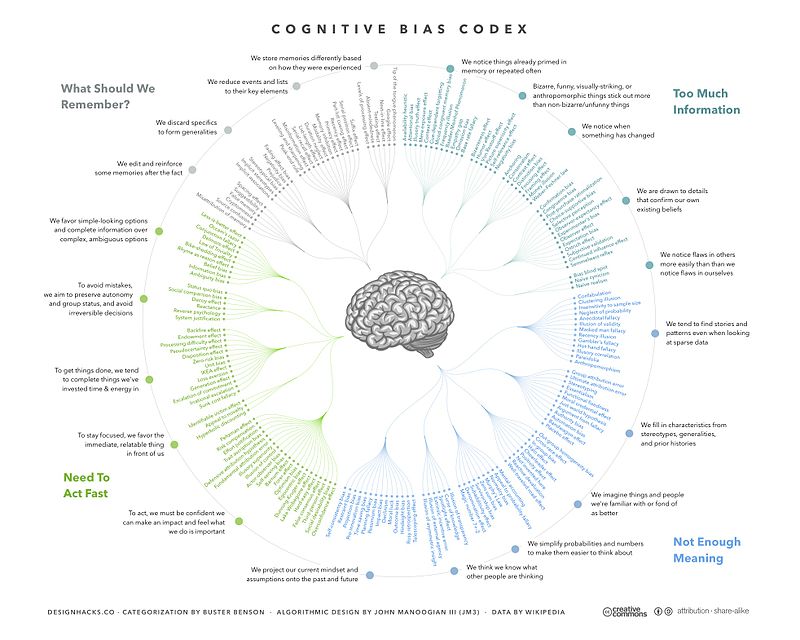

So … there are many psychological and behavioral forces at play when we engage with audiences on meaningful social issues. The important thing is to figure out what those forces are so messaging can help navigate them. You don’t need to know their official name—just what the results are when they are present. If you must figure out what it means when someone can’t seem to get motivated, you can check out this mini glossary. It’s like diagnosing yourself on WebMD for communicators. There is also a handy chart below to give you food for thought.

Designed by John Manoogian III (jm3), 2016. Categorization by Buster Benson.

Here are some questions to explore to understand what might be at play:

- What is your relationship to the group you are messaging to? Are you members of the same tribe or do you wear similar badges? Is this a “we” conversation? Or are you an outsider and what impact does that have on the communication dynamic?

- In the past when you have engaged with these audiences on this topic, what were some of their reactions? What seems to interest them? What concerns them? Ask them: What do people not get about this issue?

- What questions do they ask about the issue? Do the questions suggest they are looking to see who else is involved?

- Do they connect the issue to their own life or does it seem distant? How relevant and salient is the issue to them?

- Do they blame someone for the problem? Do they have empathy for the people who are most impacted or do they see them as others?

A reminder: When assessing what might be at play, seek out diverse viewpoints. Different people from different backgrounds and life experiences will offer different insights and intel. You’ll get a more thorough assessment by seeking multiple perspectives.

Take advantage of the forces working in your favor and minimize those that are problematic. Stop yourself if you ever find yourself saying about audiences you are trying to engage, “Why are they operating against their own self-interest?” Why are you assuming you know better what their best interest is than they do? You are missing something important. Listen. You need to figure out what you’re missing if you want to find ways to successfully engage and not get tuned out.